The hotel lobby was adorned with plum and evergreen hued midcentury modern upholstery, elegantly arranged, so I looked out of place sitting in my flared jeans and dirty tennis shoes. Across from me, my mother sat with one leg lazily propped up, looking at me as I sipped on my hot coffee with “a splash of oatmilk,” an extra dollar luxury I can only afford when my mother is in town, footing the bill. “I’m so proud of you,” she smiled. I had just told her I’d broken up with a boy.

I wasn’t sure how my mother would react to the news. Exempting her love of rom-coms, my mother is not much of a romantic. She didn’t ask what happened, or how I was. Really didn’t say more than those five words:

“I’m so proud of you.”

Her words didn’t have anything to do with him. They had everything to do with me. She was proud of me for making a difficult decision of my own accord and having the confidence to follow through. In this regard, I too was proud of myself. It is because of my mother that I am not afraid of bold decisions or dramatic change.

My mother is one of the few people I know who is not afraid of goodbyes.

When I ask my mom why she’s not afraid of goodbyes, she says she got it from my grandmother, who stood strong and didn’t shed a tear when my mom left China to come to the United States forty years ago. Is this fearlessness genetic? Growing up, no matter how hard I searched, I couldn’t find a crumb of my mother’s fearlessness in my personality. As it turns out, her characteristics have simply laid dormant for the past two decades. In my twenty-first year of life, I see that I am increasingly my mother’s daughter.

Although I hadn’t done it fearlessly, I had done a hard thing: I said goodbye.

Finding flecks of my mother’s boldness within me has been a very new trend. Besides inheriting her round face, she and I are polar opposites, so much so that I used to think our differences were irreconcilable. A five foot one Asian woman, my mother’s energetic personality makes up for her short stature. Perpetually dressed in vibrant colors, our house is always open to dinner parties for the adults and dumpling-making events for the neighborhood kids. She has a rare knack for making people feel safe and is known to be a trustworthy keeper of secrets. Even strangers feel comfortable divulging their vulnerabilities to her. As an introvert, she not only mystified me, but I coveted her social grace. Once, when I asked her about it, she said, “I’ll teach you,” but I shook my head, convinced social intuition was simply a trait I was born without, that awkwardness and social anxiety were intrinsic to me. Yet, as I get older, this delineation between nature and nurture has blurred substantially.

How much of our character is malleable? How much is fixed? Early in college, I hunted for answers in novels, curriculums, and conversations because I wanted to know who to blame when life went awry. Can I point to my environment? How I was raised? Or do I have to shoulder the responsibility for every wrong decision, every failure? The closest I got to an answer was the mistranslated word “timshel,” “thou mayest” from East of Eden by John Steinbeck, which says “the way is open.”

The more I grow up, the more I realize goodbyes are a constant in life. As a college junior, who’s becoming increasingly independent, I’m acutely aware of how often I must say goodbye to my mother now. It’s a few days together here, and a few days there, always followed by a goodbye. My mother is stronger than I am. No matter if it’s for a month, a year, or indefinitely, her eyes always remain dry, while mine glisten.

The boy I broke up with used to bring up how we both had older parents –a fact I’d never previously considered: their generation is further than ours, they’re wiser, but their health also wanes quicker. After those conversations, I’d think about how my ultimate goodbye with my mother will likely come quicker than my peers.

A few months ago, when Orion twinkled in the clear New Hampshire August, I held back tears as I laid on my back, side by side with my mom on the carpeted floor. In the sticky summer air, my tie-dye t-shirt was dark with sweat and the impending threat of junior year hung over our heads. It was my last day at home before heading back to school. As we stared at the ceiling fan, idly chatting, she was telling me about her sciatic pain; how pain is just a constant in her life these days. She wasn’t complaining, merely noticing a shift in her life. We often chat like this now, more akin to old friends than parent-child.

As she spoke, a terrifying thought dawned on me. It’s a realization which tends to hit me when I am overwhelmed with love. “Mommy,” I whispered, “can you make sure you stay healthy?” I didn’t want to say the words “what if you die?” afraid those three letters would jinx something in the universe. As I grow older, the threat of death seems exorbitantly less far-fetched, and I’m reminded that one of these days I will have to live a life without my mom.

My question was met with silence. Finally, “of course, I will.” I tried to still my face, but my lips trembled regardless. A tear leaked out the side of my eye. “I just feel like something’s always going wrong, your blood pressure, a pre-diabetic scare, and now sciatic pain.” She took my hand, and her voice was steady. “Meimei, as I get old, I will fall sick. You will take care of me…I hope so at least,” she winked, “And one day, I’ll pass. I will die. That’s okay. 没有事儿的。There’s nothing to worry about.” She said all this gently, but with a shrug. She stated it nonchalantly, as if she was relaying the time: 9:54pm. To my mother, goodbye, regardless of temporary or permanent, is just a simple fact of life, one she doesn’t dwell on or mourn.

I am not yet as strong as her, although I try to be.

A few months later, when I said goodbye to the boy, I felt helpless. I ended our conversation with, “I’ll let you go,” and went to bed that night thinking about how I meant those words in more ways than one. As night turned to day, I lay tossing and turning, filled with doubt.

Today, I realize the question of nature or nurture is a relatively pointless one. It doesn’t matter if my mother’s boldness is written in my DNA or inhaled into my lungs. Regardless of how, my mother has gifted me the ability to stand strong in the face of change. Like most, my early twenties are chock full of change, and, only now, do I realize the value of having her fearlessness.

When I told my mom about the breakup, she didn’t rub my back or buy me ice-cream. Instead, she shrugged her shoulders, as if to say “life moves on.” With my friends, all early twenty somethings, we speak about everything like it’s the end of the world. In contrast, I found her casual response to be grounding. Afterwards, we talked about my ambitions and the adventures my future may hold. She lets me talk selfishly about my life for hours on end, and when I’m with her, I feel like my potential is endless. Both our eyes shine with possibility. Pumping her fist in the air, she frequently proclaims “Go, Meimei, go!” I can hear her voice so clearly in my head.

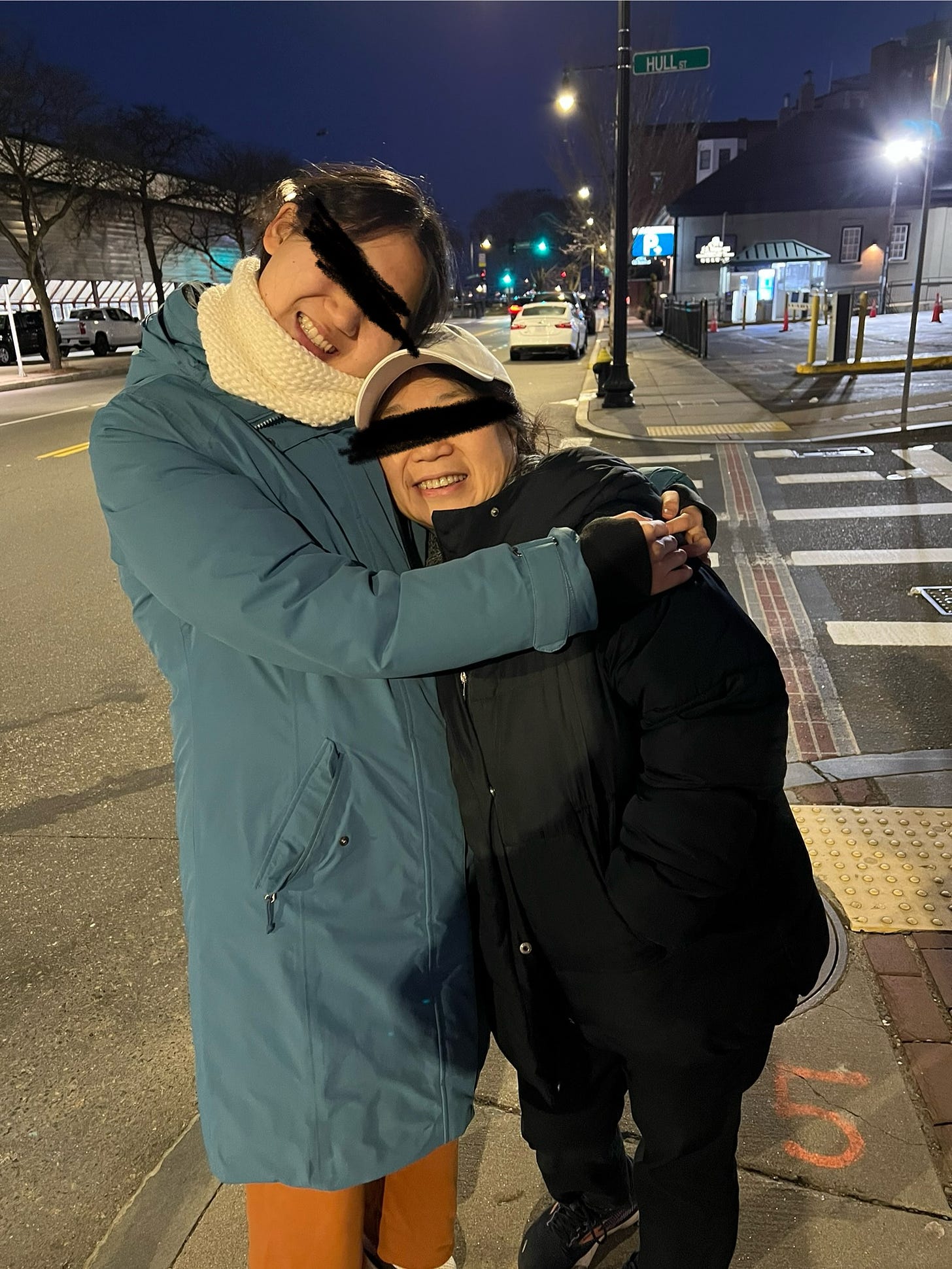

At the end of the weekend, I carried bags full of groceries back to my room, another luxury of her visits. Finally, the trunk was empty, and we stood outside, in the February cold. Her goodbyes are swift; she doesn’t like prolonging our parting of ways. After less than forty-eight hours together, she hugged me tight and told me, “I hope you have enough energy to study now,” with a twinkle in her eye. To be honest, after shoveling down an entire slice of chocolate coconut cake with her, I felt kind of lethargic. She held me tight and then, she let me go. “I love you,” she said. “I love you, too,” I responded. I tried to emulate her. Refusing to loiter, I turned and walked away.

As I stood in the frigid elevator back to my dorm, I profoundly missed her. Complementary to goodbyes, missing people is a feeling that’s becoming all too familiar. I’m always missing someone. When I got to the third floor, I peered out the window to see if I could still see her rental car. Her parking spot was empty. She was gone.

When I consider my mother growing older, I become increasingly terrified of how much I’ll miss her when she’s gone for good. But, her strength whispers to me that farewells pass like seasons change. Goodbyes are hard, but hard things are not inherently good or bad; sometimes they’re a neutral part of life, like washing dishes or doing laundry. I can’t tell if my newfound embrace of goodbyes is because of nature or nurture, but I am my mother’s daughter, so maybe it’s both. I still find goodbyes to be sad, but I am no longer afraid of them. When she eventually passes, I will weep, but I will not tremble. Goodbyes and dramatic change are two sides of the same coin; love transcends both.

"i'm always missing someone" same girl, same. here for u always!